Hiring the Illegible

Part 1: Build a Talent Community around you

Hiring is not like buying software

There are two ways to be wrong about hiring. The first is to say "we want the best people" without defining "best" or acknowledging that each additional bullet point on a job description has a cost. It is a market after all.

The second is to treat hiring like buying software : spec out what you need, review a bunch of options, pick one.

The market for full-time employees is different in two important ways:

Talent is 100% rivalrous. The purchase of software is mostly nonrivalrous. It’s not important that you beat other buyers to the purchase—in fact, if you get there after someone else, you’ve probably de-risked your purchase. But only one company can hire any given full time employee at any given point in time.

Two-way selection process. Software vendors are unlikely to turn down your business so the buyer is the one with selection power. Hiring is a two-way street. You choose your employees, and your employees have to choose you. That means foreclosing on other people and opportunities.

Hiring is a lot more like dating (to monogamous ends) than it is like buying software.

Startups face unique challenges

If the market for talent is hard for everyone, startups face a few additional challenges:

Good and bad hires are more consequential. At a 10-person company, each employee is 10% of the workforce. Their output, judgment, and behavior shape the trajectory of the company in ways that dwarf the marginal impact of the median employee at a larger company.

Weak brand recognition and adverse selection. Even well-funded, fast-growing startups are unknown to most candidates. The talent you want doesn’t know you exist. They’re probably not going to find you through a job board or inbound application. The pool that does find you through open applications has a higher share of the desperate and the habitual spray-and-pray-ers.

Novel problems are less legible. A startup exists to manifest novelty in the world. That might entail the creation of a new category or a slight but surgical tweak to an old one. Incumbents know what work needs doing, so they've carved it into jobs. You're still figuring out the shape of the problem—which means you need people before you can describe the role

So: the stakes are high, the people you want won't find you, and you can't find them by keyword matching.

The upshot: Illegibility runs both ways

As a startup, you’re illegible to the market. But the market is also failing to see and price talent that might be perfect for you.

Large companies are where legibility gets produced. A recognizable name and a standardized role give the rest of the market a shortcut for evaluation. So those signals become the default filter; not because they’re equally predictive everywhere, but because they’re easy to read.

Large companies filter the way they do because they need hiring to be scalable and defensible.

This creates systematic blind spots for everyone:

Path dependency. The right school leads to the right first job leads to the next. Each signal opens the next door. But if you missed an early gate—or took a non-standard route—the market will price you at a discount

Arbitrary domain restriction. Ability transfers across domains, but the market filters by domain and really, any keyword it can use. So people with relevant skills get filtered out because they lack the labels. For example, someone doing performance attribution or manager selection at an asset allocator is likely to have a bunch of relevant skills for data science at a tech startup—but I know that these resumes rarely get through filters.

Adaptive for large companies = (sometimes) maladaptive for startups. Impatience with process. Intolerance for bureaucracy. Disagreeableness. Large companies filter out these traits or stall their progress. These are features not bugs in early startups.

The not-looking. The people you want are probably doing something else and doing reasonably well—but that doesn't mean they're doing the thing they're most excited about, or that fits best with their skill set. “I’ll consider if something great comes along” is a common posture and the willingness to jump changes based on personal factors and specifics of the opportunity.

Time Pressure Kills Quality

If you need to hire for role X right now, you’re stuck: either resort to the adversely selected pool or compete for highly legible talent by paying a premium. The people you actually want—the illegible talent, the people who aren’t looking—require time and context to find. They take longer to evaluate and longer to convince. You need relationships to reach, evaluate and close.

Sourcing Strategy

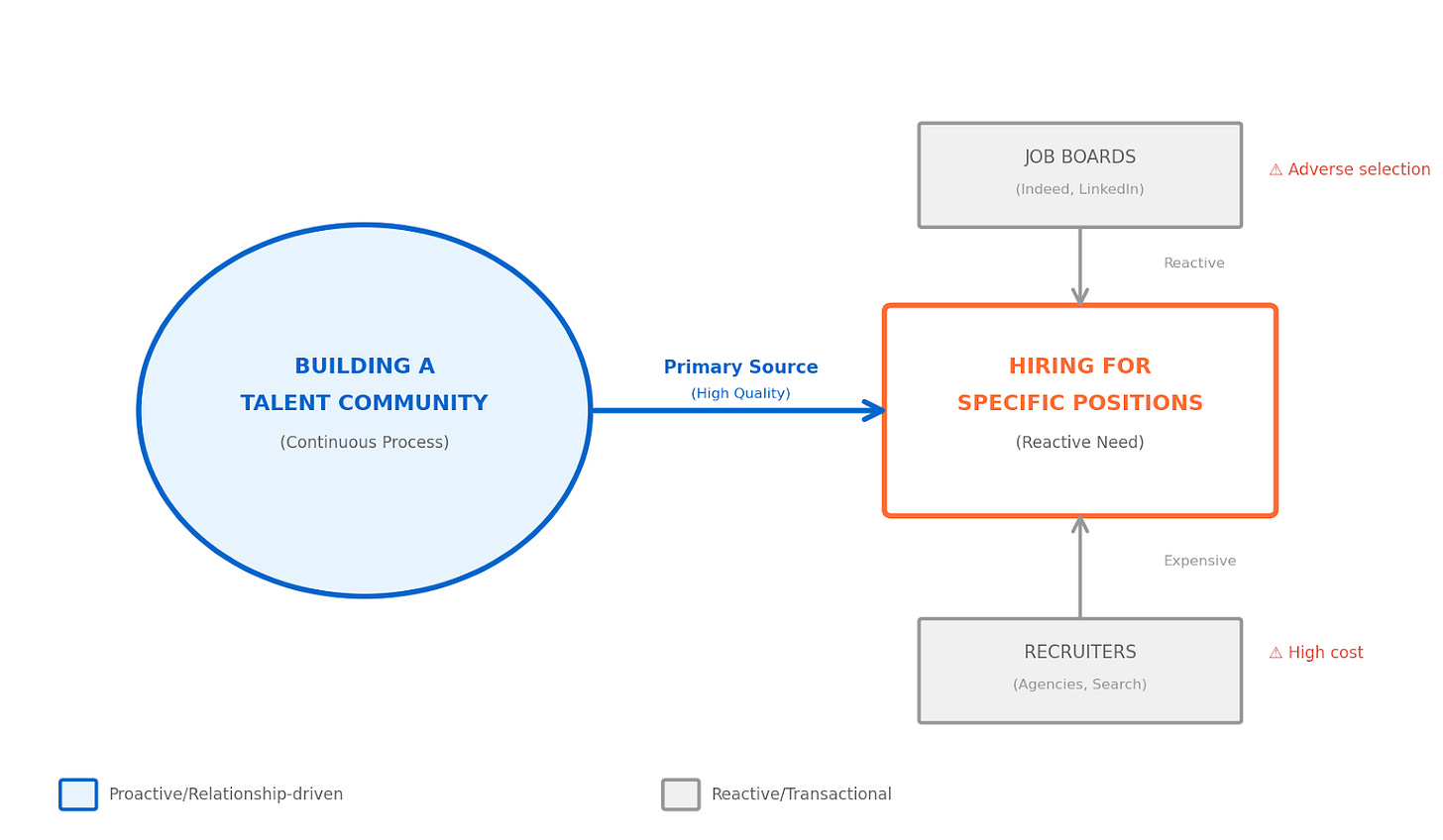

The earlier you are as a startup, the more it makes sense to think of sourcing not as the process of filling specific roles but as one of building a network/community of talent around your organization.

Doing this successfully means that you can hire opportunistically when excellent talent becomes available, and it means that when a position needs to be filled, you have at least a few candidates whom you have quite a bit of context/signal on.

Building your Own Talent Community

There are two complementary ways to build this community.

Inside Out: Start with your existing social capital—founders, employees, advisors—and expand outward by asking “who’s great?” Networks encode information that’s hard to articulate. When someone recommends a person, they’re implicitly filtering for taste, judgment, work style, cultural fit—things that can’t be captured in a job description.

Outside In: Make yourself visible in places with a disproportionate share of people who fit—in terms of both skills and disposition.

The two reinforce each other. The network points you to communities; the communities generate new nodes for the network.

Implementing the Inside Out Model

Start with your initial nodes: co-founders, early employees, advisors. From these nodes, you’re trying to generate two types of recommendations.

The first is meta-level: people with good taste, good judgment, and access to talent. These are sources of future recommendations. Call them talent scouts.

The second is object-level: actual talent. People who might be right for a role now or in the future.

Both are valuable. And once you’ve built a relationship with someone—whether they become a hire or not—they become a potential source of further recommendations.

The network expands outward.

One useful tactic, especially for roles you don't know well: approach senior people explicitly not as candidates, but as advisors. "Assume you're not looking, but I'd love your advice on how to think about talent in this space." This gets you context on where to look and what to look for—and it opens the door to recommendations without the awkwardness of asking if they know anyone like themselves, but earlier in their career.

When someone joins the company, one of the first things you should do is ask them for talented people they've worked with. They're excited, their network is fresh in their mind, and they want to help build the team they're joining. But just as important: give them an easy way to send names your way as they think of people later.

Managing the recommendation flow

As you start generating recommendations, three principles to keep in mind:

Protect reputation. People need to look good when they send someone to you. In the early days, this means a senior person—founder or close to it—meets everyone who gets referred. Have open-ended, transparent conversations: “We’re still figuring things out. I’d love to learn about what you’re looking for.” Don’t lead anyone on. And close the loop with the referrer so they know their recommendation was taken seriously. Over time, you can be more selective—but initially, treat every referral seriously, or people stop sending them.

Reduce friction. When you put people on the spot—”who do you know?”—most blank out. Don’t require immediate answers. Leave the door open: “Anytime you think of someone interesting, just text me.” No forms, no portals. The barrier should be as close to zero as possible.

Learn over time. As the network develops, you’ll see patterns: the employees with interesting friends, the scouts who generate high-quality introductions, the networks that align with your taste. This lets you prioritize the high-signal sources. But you need data before you can make these distinctions, which means keeping your scouts happy until you know who they are.

Implementing the Outside In Model

Inside-out builds from existing relationships. Outside-in is more deliberate: you go looking for specific types of talent.

The key is to think broadly about selection effects. The obvious starting point is communities organized around specific skills (data science meetup, RUST discord etc) But for talent that’s harder to define - imagine your ideal employee and ask: What newsletters do they read? What podcasts do they listen to? What events do they attend? What open-source projects do they contribute to? What weird corners of the internet select for the traits you actually want?

One practical starting point: survey your existing employees—what do they read, listen to, follow? Then use that to find adjacent communities. You can even paste the list into Claude and ask “if someone likes X, what else might they like?”—a rough way to surface places that might prove generative.

But once a place becomes a known talent source or a de facto job board, it loses most of its selection.

What you want are incipient communities—emerging podcasts, newsletters, meetups, reading groups, niche Discords. Finding them requires curiosity and time. But once you do, organizers are often eager to partner: these places are usually undermonetized. Speak at their event, sponsor a meetup, buy an ad in the newsletter. Most of these groups are happy to do something ad hoc if you just ask.

Sending the right signals

While engaging with these spaces, the goal is to make the company memorable to the right people for the right reasons.

Networking is sending hard-to-fake signals. You want to put something out there that reveals what makes you interesting. A contrarian position on a niche technical issue. A norm or cultural stance where you disagree with the general Silicon Valley consensus. Something with personality.

Instead, people default to:

“My co-founder is exceptional” — of course you’d say that

“We move fast” — what startup doesn’t say this?

“We have high standards” — free to claim, costs nothing

It’s also become fashionable to brag about how intense your culture is. This does filter—but it turns away people who don’t like performative intensity without giving serious people anything specific or falsifiable to evaluate. Intense about what? Driven by what?

It’s useful to remember that bold claims without specificity or evidence are not neutral. They’re often read as a negative signal.

Keeping Talent Warm

Initial meeting. Someone in the company meets with them. The conversation is open-ended, exploratory. You’re learning about them, they’re learning about you. Be transparent and non-committal: “We’re still figuring things out. I’d love to understand what you’re looking for.”

Add them to the community. If you like them, they go into your talent community: invited to events, receiving occasional updates, on your radar for future roles.

Assign a point person (for those you’re particularly impressed with). For people you’re especially excited about, someone in the company owns the relationship. They check in periodically. They watch for timing—new manager, shifting circumstances, openness to moving.

Make it easy for them to refer others. Everyone you meet is a potential scout. Even if they’re not right for you, they might know someone who is. Keep the friction low: “If you ever meet someone great, just text me.”

Events as ongoing touchpoint. Quarterly (or whatever cadence), invite the community to something low-key—pizza and beers at the office. You get to see people in a relaxed context. They get to see you. It keeps the relationship alive without constant 1:1 outreach.

Who the fuck has time for this?

There’s no getting around it: founders and early employees have to be deeply involved in talent. What I’ve described requires systems, time, and taste.

If you have the funding and expect to hire more than 10 people in the next 18 months, it’s not crazy to hire someone to own this.

To beat the horse that’s long dead: Labels and categories can be unhelpful. Instead of calling this person a ‘recruiter’ or ‘talent ops’, we can start by listing what you want done:

Strategic: A thought partner who helps map problems to people. “Do we actually need a full-time hire here, or is this better contracted?” “Should we look for a generalist or a specialist?” This requires understanding your organizational context—not just executing a search.

Social finesse: Someone who can be a credible face of the company to candidates and build relationships before there’s a role to fill.

Content and communication: Outbound recruiting is fundamentally a copywriting problem. This person writes outreach emails (often on behalf of the CEO), makes contact with creators and communities, and may create content that makes the company visible to talent.

Managing external resources: For specialized roles, you’ll engage external recruiters. There’s broad variance across agencies. Someone needs to select the right partners and manage these relationships—without judgment here, you’ll waste time on the wrong ones.

One exception: if you’re hiring specialized technical talent from a narrow domain, a recruiter with deep networks in that space—or a technical person who can evaluate candidates—might matter more.

For most startups, what matters is the ability to leverage the organization’s existing social capital: mining the founders’ and employees’ networks, turning every new hire into a node for further connections, converting early wins into inbound interest.

Pure agency recruiters are probably not a good fit. In-house experience is better. But the best fit is often someone who’s built something themselves: a bootcamp, a community, a small business. They’ve done the work of attracting and evaluating people without a brand to lean on.

In the next part of this series, I discuss the incentives of external recruiters and evaluation tactics.